Detroit has long been defined by the roar of engines and the rhythm of the assembly line. For generations, the city’s identity was forged in steel and gasoline. However, a quiet but profound transformation is underway across Southeast Michigan. The Motor City is rapidly evolving into a global center for Detroit cyber-physical systems (CPS), a shift that is fundamentally altering how local businesses operate, how vehicles are built, and how the city itself functions.

Cyber-physical systems represent the intersection where the digital world meets the physical one. These are not just computer programs running in a cloud; they are smart networks where algorithms control physical machinery, traffic lights, power grids, and autonomous vehicles. As the automotive industry pivots toward electrification and autonomy, Detroit is positioning itself not just as a manufacturer of hardware, but as the primary architect of the intelligent systems that power it.

According to data from Automation Alley, Michigan’s Industry 4.0 knowledge center, the integration of these systems is crucial for the survival and growth of the state’s manufacturing base. The organization notes that the adoption of CPS technologies is growing at an unprecedented rate among small to mid-sized manufacturers in the region, creating a new ecosystem that blends traditional engineering with advanced computer science.

The New Industrial Revolution in Detroit

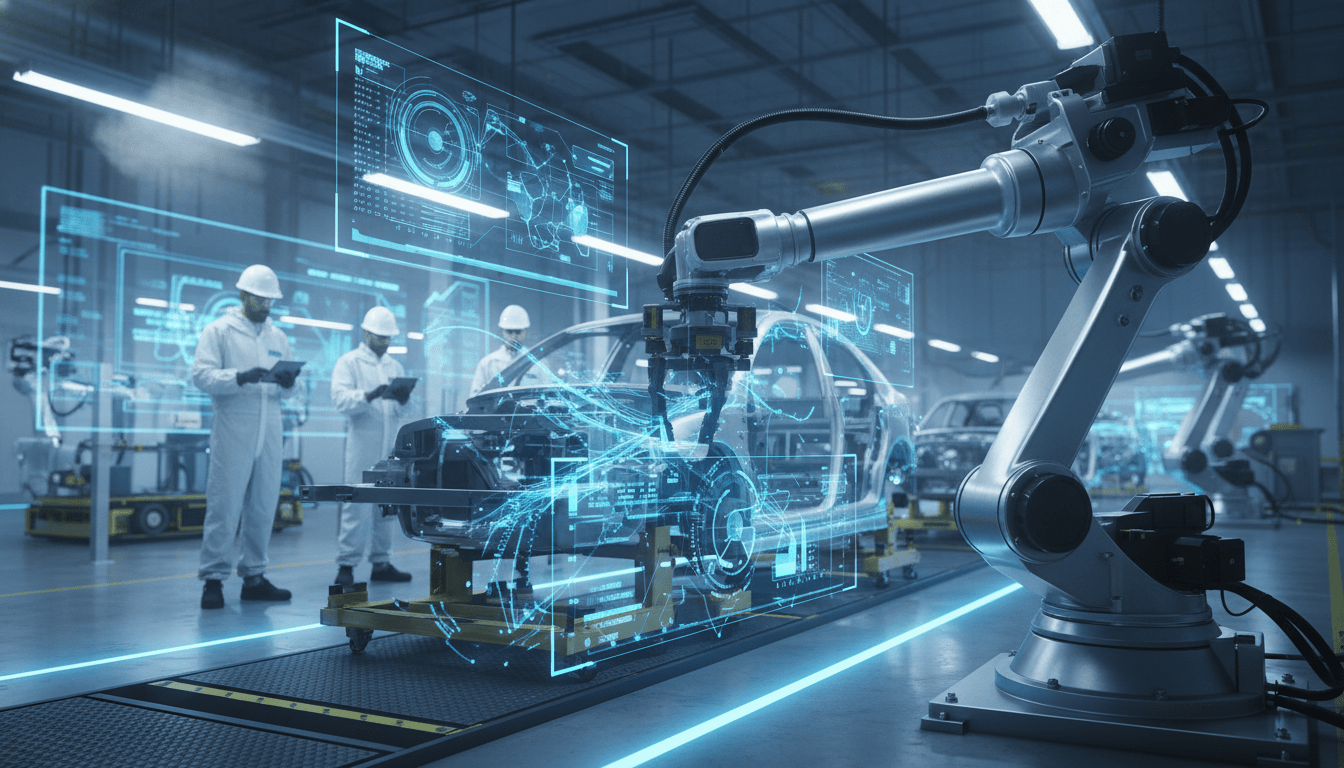

The concept of Industry 4.0 is central to understanding the boom in Detroit cyber-physical systems. In traditional manufacturing, a machine simply performed a repetitive task. In a cyber-physical environment, that machine is equipped with sensors, connected to a network, and capable of making real-time decisions based on data.

“We are seeing a transition from purely mechanical engineering to a hybrid model where software drives the physical process,” said a representative from the College of Engineering at Wayne State University, which has been ramping up its robotics and CPS curriculum. “This isn’t science fiction; it is the current reality of the factory floor in Detroit.”

This shift is visible in initiatives like Project DIAMOnD (Digital, Independent, Agile, Manufacturing on Demand). Spearheaded by Automation Alley and funded by Oakland County and the state, this initiative has distributed hundreds of 3D printers to local manufacturers, linking them into a massive distributed network. This allows for the rapid production of parts in response to supply chain disruptions—a perfect example of a cyber-physical system in action.

For the Detroit automotive industry, this means that the factories building the next generation of EVs are becoming as complex as the vehicles themselves. General Motors’ Factory ZERO and Ford’s Rouge Electric Vehicle Center utilize advanced CPS to monitor robot health, predict maintenance needs before breakdowns occur, and optimize energy usage in real-time.

Mobility: The Ultimate Cyber-Physical System

While manufacturing is the backbone, the most visible application of Detroit cyber-physical systems is on the road. Autonomous and connected vehicles are, by definition, cyber-physical systems. They perceive the physical world through sensors (cameras, LiDAR, radar), process that data digitally, and execute physical actions (steering, braking).

The development of the Michigan Central innovation district in Corktown highlights this focus. Ford Motor Company’s restoration of the train station is not merely a real estate project; it is designed to be a testing ground for mobility solutions. Here, infrastructure talks to vehicles, and vehicles talk to pedestrians’ devices. This “V2X” (Vehicle-to-Everything) communication is the frontier of CPS technology.

Local urban planners suggest that this technology will eventually integrate with city infrastructure to improve traffic flow and safety. “The goal is a cohesive system where traffic signals adapt in real-time to congestion, communicating directly with oncoming vehicles,” a spokesperson for the Detroit Department of Public Works noted in a recent infrastructure briefing. “This reduces idle time, cuts emissions, and improves safety for Detroit residents.”

Impact on Detroit Residents and the Workforce

For the average Detroiter, the rise of cyber-physical systems brings both promise and challenge. The most immediate impact is on the job market. As factories become smarter, the demand for traditional unskilled labor is shifting toward roles that require technical literacy.

The Workforce Intelligence Network for Southeast Michigan has highlighted a growing gap in talent for roles specifically related to robotics maintenance, systems integration, and data analysis. This does not necessarily mean that jobs are disappearing, but they are changing. A worker who once manually inspected parts might now monitor a bank of sensors that do the inspecting.

To bridge this gap, local institutions are stepping up:

- Focus: HOPE has continued to evolve its training programs to include IT and robotics, ensuring that Detroiters from underrepresented communities have access to these high-paying fields.

- University of Michigan and Wayne State University are partnering with local high schools to introduce CPS concepts early, demystifying the technology for the next generation.

“The narrative that robots are taking all the jobs is incomplete,” said a local workforce development officer during a recent town hall on economic development. “The robots need people to program, maintain, and optimize them. The cyber-physical economy creates high-quality careers, but we must ensure every neighborhood in Detroit has the pathway to access them.”

Furthermore, the implementation of CPS in city services promises a higher quality of life. Smart street lighting that reports its own outages, water systems that detect leaks instantly via pressure sensors, and responsive waste management routes are all on the horizon for a “smarter” Detroit.

The Role of Academic and Federal Support

Detroit is not acting alone in this transition. The region is supported by significant academic and federal investment. The National Science Foundation (NSF) has long recognized the Midwest as a critical hub for cyber-physical research. Grants flowing into the University of Michigan and Michigan State University are often piloted in collaboration with Detroit-based industry partners.

These partnerships ensure that the technology developed here stays here. Unlike Silicon Valley, which focuses heavily on software, Detroit’s competitive advantage remains its ability to build physical things. The fusion of the two ensures that the region remains indispensable to the global economy.

Looking Ahead: The Connected Future

As 2025 progresses, the integration of Detroit cyber-physical systems will likely accelerate. With the expansion of local tech startups focusing on IoT (Internet of Things) and the continued investment from the Big Three, the city is shedding its Rust Belt image for one of high-tech resilience.

The challenge remaining for city leaders and business owners is ensuring inclusive growth. If Detroit can successfully upskill its workforce and apply these smart systems to improve neighborhood infrastructure, it will serve as a model for how legacy industrial cities can thrive in the digital age. The Motor City is well on its way to becoming the Mobility City, powered by the invisible, intelligent networks of the future.